Pessimism About U.S. Growth Rates

A growing number of observers are starting to conclude that we’re never going to see the rebound in growth rates that many people had anticipated as the U.S. recovers from the Great Recession. Here I comment on a new paper in which Northwestern Professor Robert Gordon explains the basis for his pessimism.

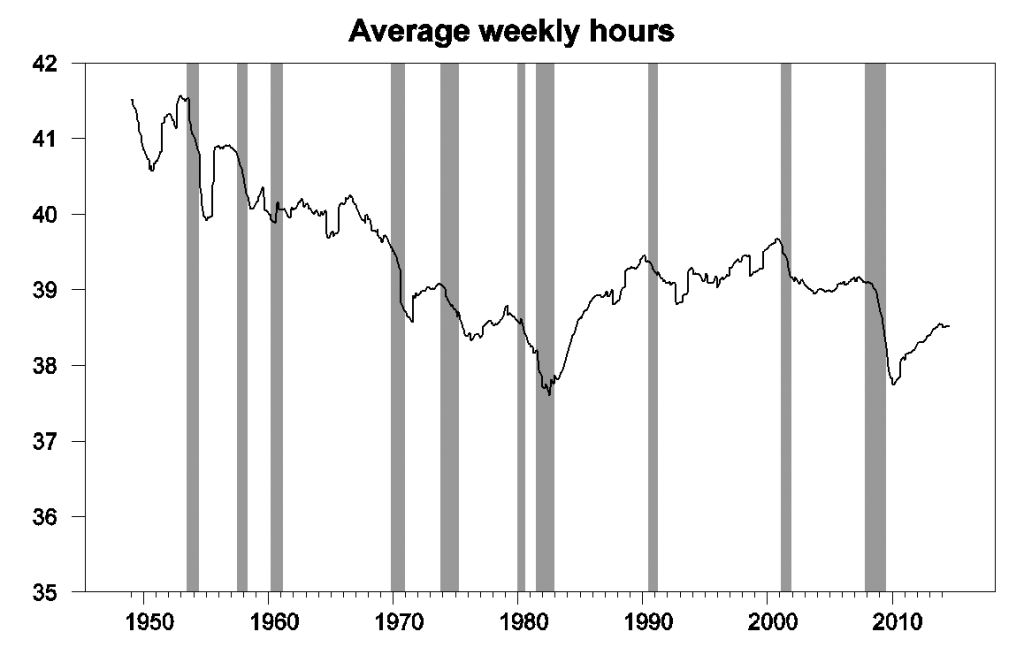

A streamlined version of Gordon’s analysis would decompose the growth rate of output as the sum of growth in productivity (output per hour worked), growth in average hours worked per employee, and growth of number of people working. We received a temporary boost to growth from the second factor as a result of a cyclical rebound in the average workweek since 2010. There might be a further modest contribution from this source if hours per worker get all the way back to their average value over 1988-2008. But more than half of any boost we might hope to see has already been realized at this point.

12-month average values for hours per worker, 1949:M1-2014:M8. Data source: BLS.

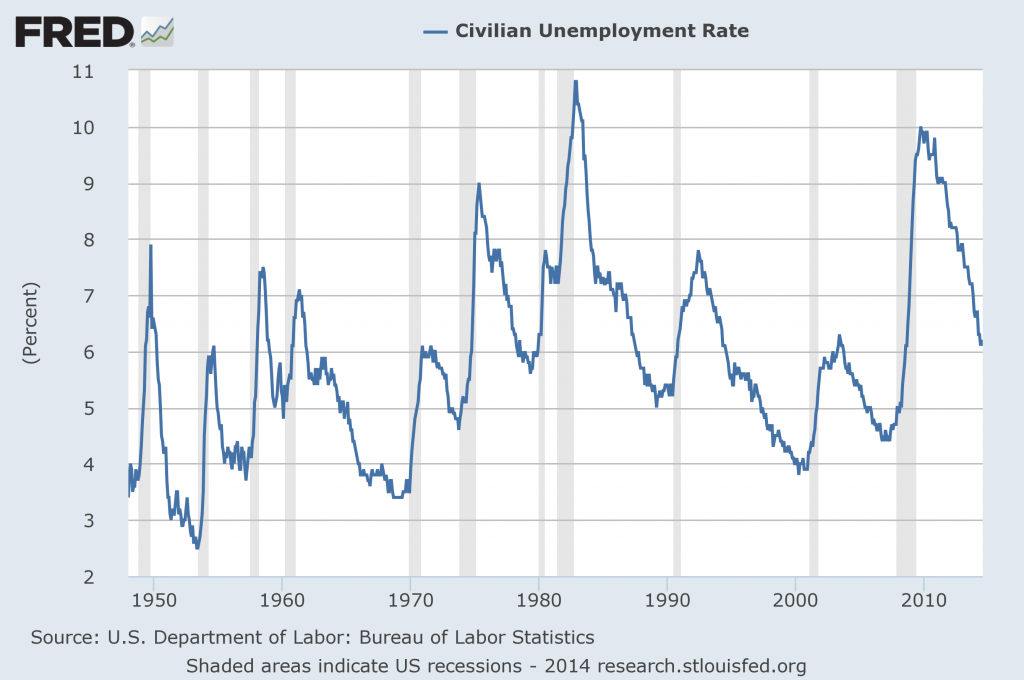

We also have enjoyed a temporary boost in growth from the third term, an increase in the number of people working, as a result of the declining unemployment rate. But with the unemployment rate already back down to 6.1%, it again seems unlikely that further drops in the unemployment rate can make a major contribution to future U.S. growth rates.

Source: FRED.

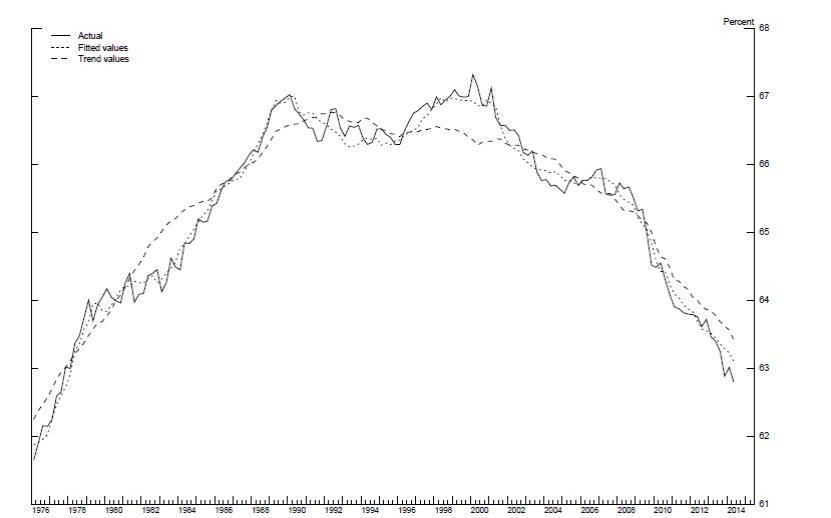

An alternative source of rising total employment would be a recovery in the labor force participation rate. But the decline in this began well before the Great Recession, and seems largely due to demographic factors that are unlikely to be reversed.

Labor force participation rate (solid) and estimated trend component (dashed). Source: Aaronson, et. al. (2014).

Thus a key factor in any prediction of faster U.S. GDP growth would seem to be based on an improvement in productivity.

Gordon writes:

Forecasters universally predict that actual real GDP growth will increase from the 2.1 percent average of the past five years to between 3.0 and 3.5 percent per year over the next two to three years. For output to grow at that rate without a decline in the unemployment rate to four or even three percent would require some combination of a much slower rate of decline in the labor-force participation rate or even a reversal toward an increasing LFPR, as well as a revival of labor productivity growth well above the 1.2 percent average growth rate of the past decade, not to mention the 0.6 percent average over the past four years.

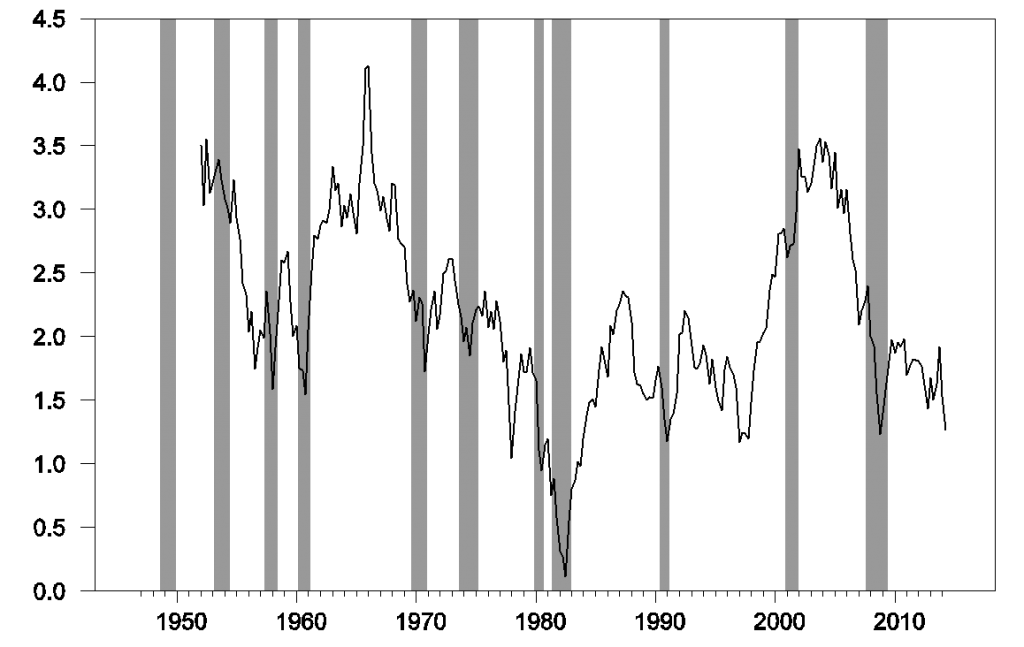

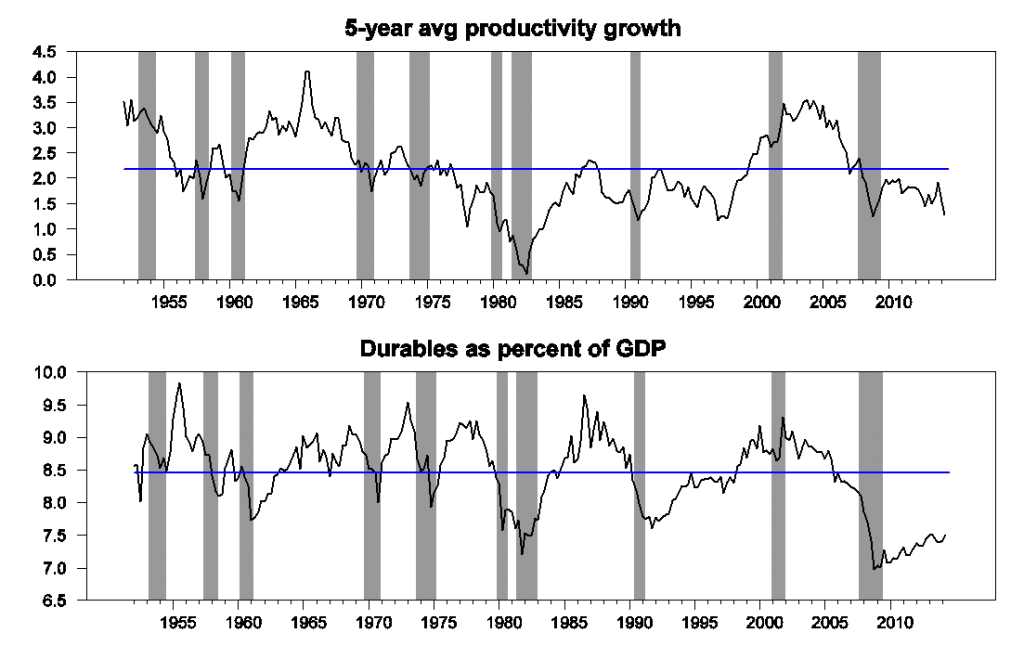

Economists usually think of long-run productivity growth as primarily determined by technological innovation and capital improvements. But cyclical factors also have an effect on productivity that extends much longer than some might suppose. The graph below plots the average growth in U.S. productivity over 5-year intervals ending at each indicated date. It’s pretty clear that these intermediate-run averages are very strongly affected by the decline in productivity associated with economic recessions and the rebound in productivity usually associated with recoveries.

Average annual growth rate of nonfarm business sector real output per worked over 5-year periods ending at indicated dates, 1952:Q1-2014:Q2. Data source: FRED.

A boost in aggregate demand can lead to higher productivity for reasons of simple accounting. Suppose you are operating a retail store and have the same number of employees today as yesterday. If more customers show up to buy today, your measured productivity (how much you sell divided by the number of hours your employees put in) is necessarily going to increase. If the demand stays high, you might find it necessary to hire more workers to meet the higher volume. But since many tasks (such as security, cleaning, and maintenance) won’t double when sales double, there will still be a gain in measured productivity when demand goes up. Something similar is true for many manufacturing facilities that have significant underutilized capacity.

The strong relation in the data between measured productivity and the strength of demand can be seen by plotting productivity together with other strongly cyclical series such as purchases of consumer durables. When consumers are trying to reduce spending, big-ticket items take the brunt of the cutbacks, and when confidence finally returns, purchases of consumer durables make up an unusually high fraction of total spending. Periods when productivity is growing slower than average correlate pretty strongly with episodes when consumer durables make up a smaller fraction of total spending than average. Durable purchases remain depressed today, and that may be a factor in continuing weak productivity numbers.

Top panel: productivity growth. Bottom panel: spending on consumer durables as a percentage of GDP. Horizontal lines represent historical averages.

To be sure, many economists interpret the causation as running in the opposite direction. They argue that if technological improvements have been particularly favorable (so that productivity growth has been strong), consumers may become more optimistic about the future, and therefore devote a higher fraction of their budgets to big-ticket items. But to me, the natural interpretation of the correlation is the traditional Keynesian one that I described above as resulting from the direct effect of higher spending on measured productivity.

For this reason, I am a bit more optimistic than Gordon. At least as far as the next several years are concerned, I side with those who expect above-average growth as consumers’ and firms’ finances continue to recover. But Gordon makes the interesting and I think correct observation that some of the U.S. economic growth since 2010 has already come as a result of factors such as a lengthening workweek and falling unemployment rate, developments that by their nature cannot be projected to continue for much longer. I agree with Gordon that the U.S. should expect a slower growth rate of potential output over the next decade than we saw in most of the twentieth century. But that doesn’t mean that we still couldn’t see better growth numbers for 2014:Q2-2015:Q4 than we’ve experienced on average over the last five years.

Disclosure: None.